As a parent, it’s important that you know how to help your young reader self-select books outside of the classroom. Like any other skill, knowing how to choose the right books takes practice. The more she practices this skill, the more likely she will be able to make good reading choices on her own.

First and foremost, a reader needs to know her strengths and what kinds of books she feels most comfortable reading. Books which are too easy for your reader will not empower her to practice new skills. Similarly, books which are too challenging will only cause her frustration. This is often referred to as the Goldilocks Principle – finding a book that is just right as opposed to one on either extreme. A just right book allows your reader to independently practice and effectively apply the reading strategies she is learning.

Learning how to self-select a just right book is a skill that needs to be nurtured and practiced. Here are 4 things that you can do at home to help your reader self-select a just right book.

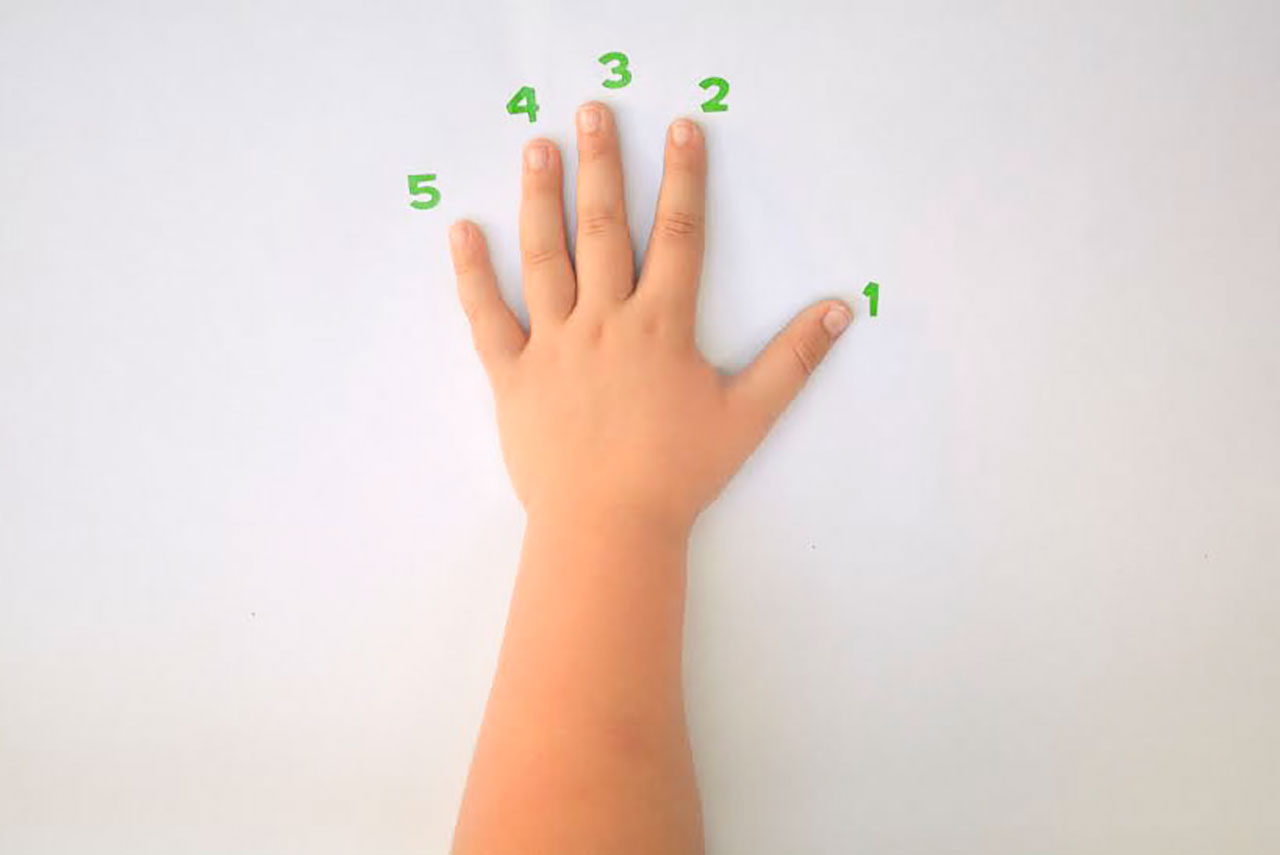

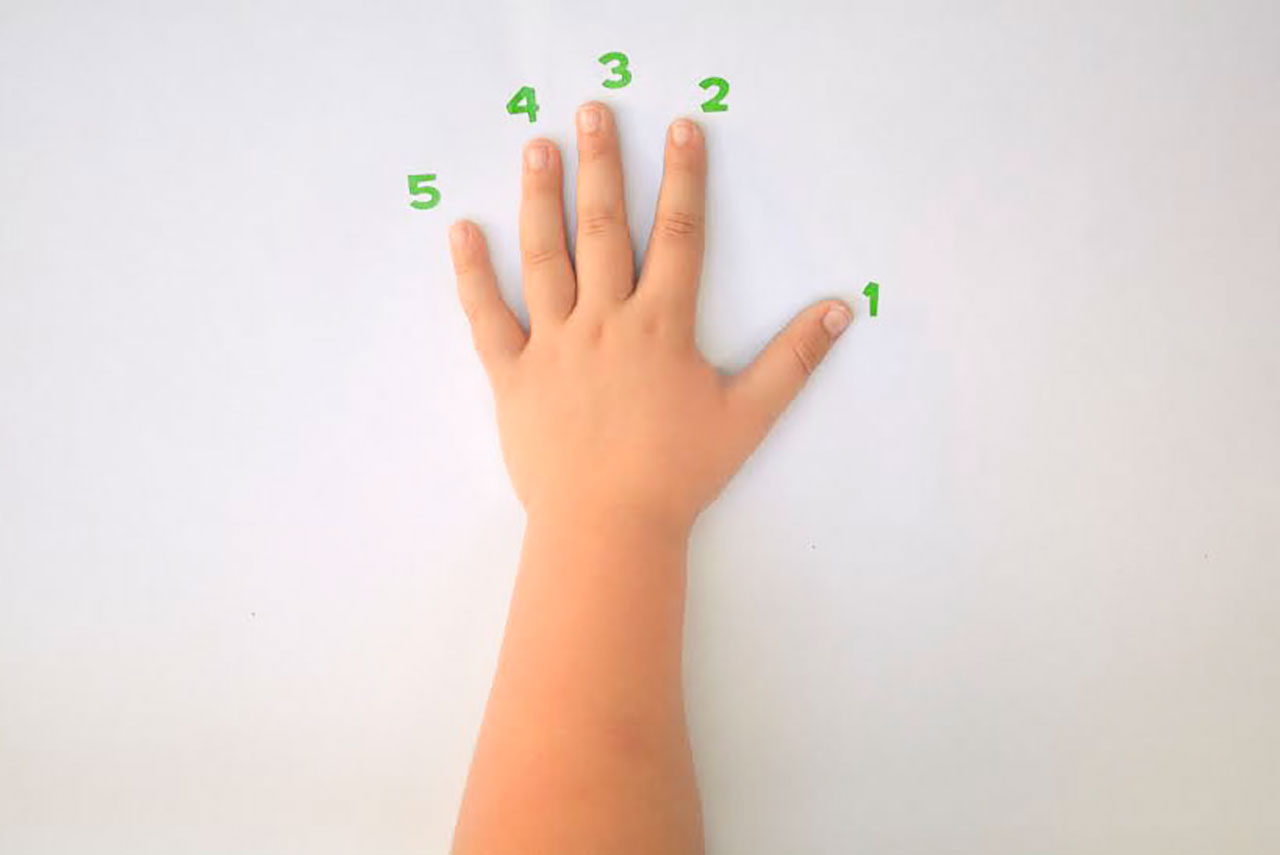

1. Try the 5 Finger Rule. This is quite simple. Open up the book to any page. As she reads, ask her to hold up one finger for each tricky word on the page. A tricky word will be one that she has trouble decoding or is unsure of the meaning. Encourage her to be honest with herself through this process. The results will usually go something like this:

0-1 tricky word – too easy

2-4 tricky words – just right

5 or more tricky words – too challenging

This is certainly not a strategy that will work for every reader, but if she has self-selected a book that is too challenging the 5 finger rule will wave a red flag that she needs to try a different book. Save challenging books for a family read aloud or have her set a goal to read it independently by the end of the school year. If the book is too easy, use it as a “warm up” to practice fluency or have her share it with a younger sibling. Your reader needs to know that it’s OK to read books on either extreme (they aren’t off limits by any means), but just right books are the ones that will help her grow as a reader.

2. Focus on comprehension not just decoding. The purpose of reading is to make meaning. Just because your reader is good at decoding words (word solving) does not mean she understands what she’s reading. Have you ever read part of a book, then stopped and said to yourself I haven’t the slightest clue what I just read? As experienced readers, we know to go back and re-read the passage again. That’s not always true for young readers. She might get to the end of a chapter, and unless someone says to her Tell me about what you’ve just read, she doesn’t even realize that she’s read 15 pages and doesn’t know what is happening in the story. Word solving does not equal comprehension. So being able to decode all of the words does not necessarily mean she’s selected a just right book.

3. Talk about age appropriate books. This may seem obvious, but believe me it’s not. Reading is a highly social activity. Many readers at this age want to carry around the newest book (because there’s a huge wait list at the library), the fattest book (because obviously the number of pages is directly proportional to the kind of reader you are), or the book that her middle school aged sister is reading (because it’s about middle school… duh). This often means that in the process, she will have a book in her hand that is not age appropriate. A good rule of thumb in selecting a just right book is if the main character is 2-3 years older than your reader, know that there may be mature themes and content that your youngster is just not ready to deal with yet (romance, death, puberty and other complex issues). If your child hasn’t had similar life experiences, how on earth is she going to identify with a character’s actions and motives?

If after much argument and eye rolling she still insists on selecting a book that is beyond her life experience, consider reading it together and talking about themes that may be too difficult for her to comprehend independently. If possible, preview the book beforehand so you know what you’re getting yourself into!

4. Try not to talk too much about “levels.” This only confuses your reader. When you tell her she’s reading at a 6th grade level it gives her the false impression that she can read anything a 6th grader can read which may not be the case (you read #2 and #3, right?). Levels also put too much pressure on your reader, and it forces comparisons with others (which let’s face it, she is doing already so why add to that?).

As adults, we certainly don’t brag about our reading levels.

This month’s book club book was way too easy for me. I went into the bookstore yesterday, and I couldn’t even find anything at my reading level. I really think I should be reading something harder.

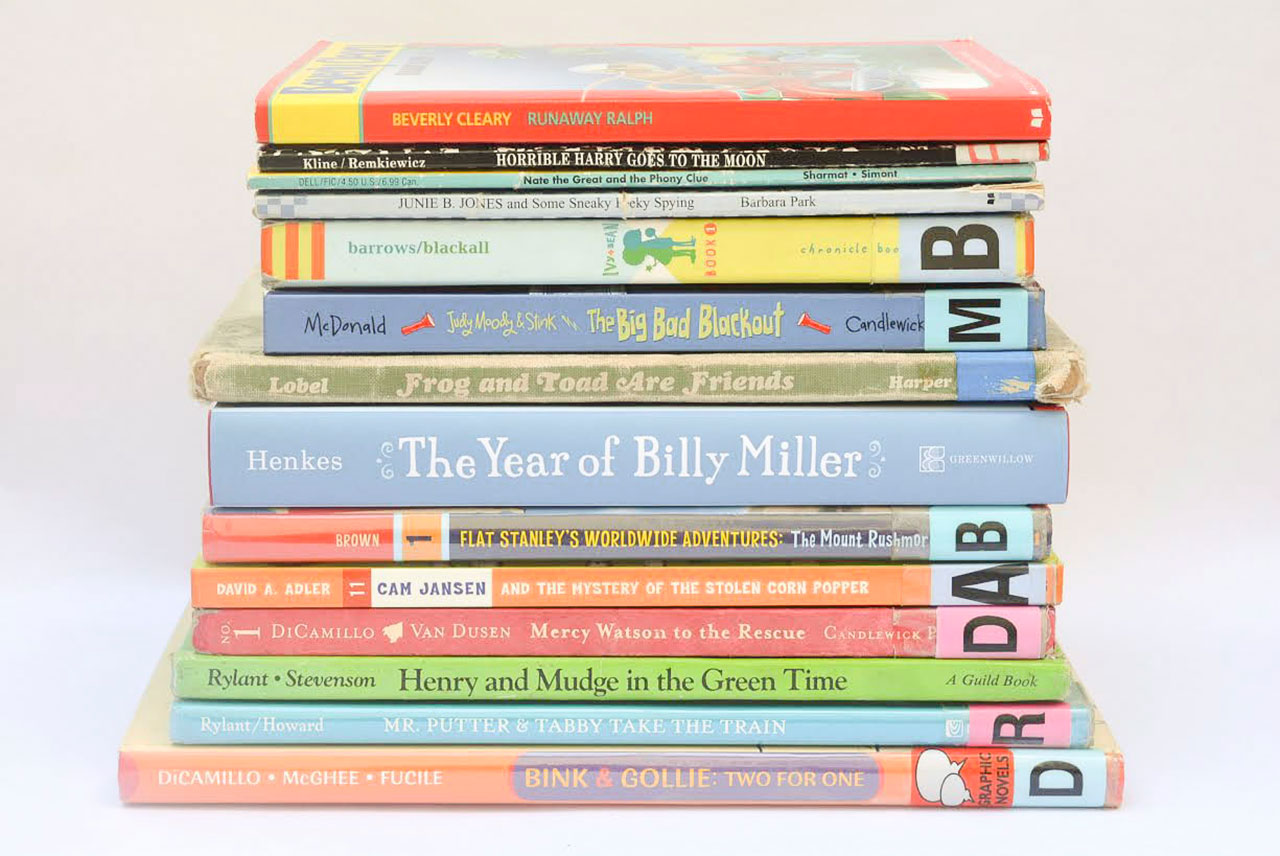

It sounds ridiculous, right? Yet that’s exactly how young readers talk to one another in the classroom when adults place too much emphasis on reading levels. Yes, we want our readers to be able to select and read grade level material. Yes, a reading level is often written on her report card. And yes, that’s usually the first part of the report card that your eyes scan for first. You want to know if your child is reading on grade level. However, we can talk about grade level expectations without labeling your reader as a number or letter. Believe me, if I could leave out reading levels on my report cards and instead just focus on a reader’s interests and abilities, I would be one happy teacher. Unfortunately, that’s not the reality in this day of standards and high stakes testing. However, my classroom readers know that they will not hear me talking about levels nor are any of my books sorted or categorized by letters and numbers. Instead we talk about choosing just right books based on our interests, our life experiences, the genres we prefer, authors and series we adore, and those which will generally help strengthen our reading skills.

As you’re helping your reader learn to self-select just right books at home, remember that the ultimate goal is to foster a love of reading. We want reading to become a welcome habit not a necessary chore. The more you help her learn how to independently choose books that are a good fit for her, and appeal to her interests and abilities, the stronger of a reader she will become.

What other things do you do at home to help your reader self-select books?